Source: archive.org

Source: archive.org“I think we’re going to have it”, current US President Donald Trump exclaimed in 2025. But over 100 years earlier, Danish and American explorers were risking their lives to establish their respective claims over northern Greenland.

Successive expeditions to uncharted areas of northeast Greenland tragically led to the deaths of one group of Danes, and another pair of explorers left abandoned and presumed dead. Furthermore, countless dogs used to support these expeditions were shot, eaten or died of exhaustion.

This is a story about this latter pair – Ejnar Mikkelsen and Iver Iversen – who miraculously survived more than 2 years of hell alone in the remote Arctic between 1910-12. To understand how they ended up trapped in the High Arctic, we must first go back 20 years to the conception of a mapping mistake by Americans and the subsequent attempts to prove it wrong.

The myth of Peary Channel emerges

Northeast Greenland still remained a blank area of the map at the end of the 19th century, essentially inaccessible due to the heavy sea ice that wraps this coastline year-round.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaAt the time, the American explorer Robert Peary was a major driving force in unlocking the geography of this Arctic region. His motivations for doing so resonated with current US concerns, particularly on national defence:

Greenland in our hands, may be a valuable piece of our defensive armor. In the hands of a hostile interest it could be a serious menace.

During his 1891-92 expedition, which tracked across the northern Greenland ice sheet, Peary extrapolated from sporadic sightings that the far northeast of Greenland was separated from the mainland by a wide channel. A discovery of a separate territory would certainly boost US claims in this region.

Subsequent maps published after the expedition embraced Peary’s observations, and the myth of the ‘Peary Channel’ was born.

Danes uncover the map myth

Between 1906-1908 Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen led the Denmark Expedition to northeast Greenland to map some of the last blank sections of its coastline. The newly discovered Peary Channel was to be investigated too.

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryBy May 1907, six Danes had reached the northeastern end of Greenland by dogsled; however, it was late in the season and supplies were already dwindling. Mylius-Erichsen then took the fateful decision to continue the survey rather than head back to the ship.

Along with Niels Peter Høeg Hagen and Jørgen Brønlund, they reached Independence Bay, which Peary had seen 15 years earlier. However, what Erichsen found that Peary had missed was that the bay terminated at Academy Glacier and was, in fact, a fjord – Peary Channel did not exist.

Sudden mild weather during the return journey had literally melted away their route home.

“No food, no foot-gear, and several hundred miles to the ship. Our prospects are very bad indeed.”

Jørgen Brønlund writing in his diary.

Forced inland to find food, their search was in vain, and one by one, they died of cold and starvation. Brønlund was the last to die. His body, along with his diary, was found the following spring by expedition members, the last entry of which read:

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibrarySuccumbed at 79′ Fjord after attempting return across the inland ice in November. I arrived here in waning moonlight and could go no further because of frost-bitten feet and darkness. The other’s bodies are to be found in the middle of the fjord in front of the glacier (about 2½ leagues). Hagen died 15 November and Mylius about 10 days after.

Bjørnlud’s diary gave no definitive clues as to their discoveries in Independence Fjord, and so the myth of Peary Channel persisted in the Denmark Expedition’s maps.

Source: Yale University Library

Source: Yale University LibraryA rescue expedition is organised

Finding the bodies of Mylius-Erichsen and Høeg-Hagen meant possibly recovering their journals and maps – data that could help settle the claim over whether Peary Land belonged to the United States or Denmark.

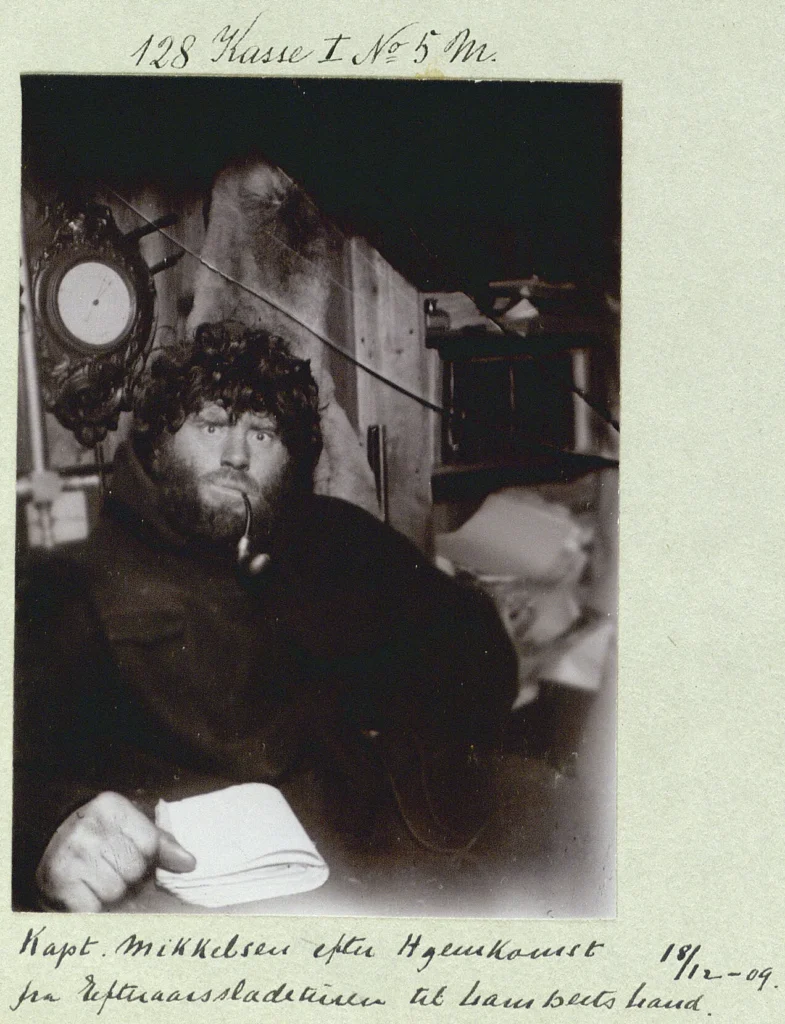

And so in June 1909, fellow Danish explorer Ejnar Mikkelsen and friend to Mylius-Erichsen set sail for East Greenland in the sloop Alabama with six men, hoping to find answers. The Daily Mail had initially offered to fund the expedition. However, as Mikkelsen wrote, as a Dane, he did not like the idea of an Englishman paying, nor that this money would acquire the rights to what three Danes had given their lives to achieve. Ultimately, the funding was crowd-sourced, with the Danish Government matching the other half.

A series of misfortunes following their departure came as an ominous omen. Firstly, the 50 dogs they had ordered from West Greenland and shipped to the Faroes all had to be shot.

They had been good, strong animals, but the hardships of the voyage and perhaps thoughtless and unwarrantable treatment had quite ruined them…we had to bring ourselves to shoot every one of them.

Source: Royal Danish Library

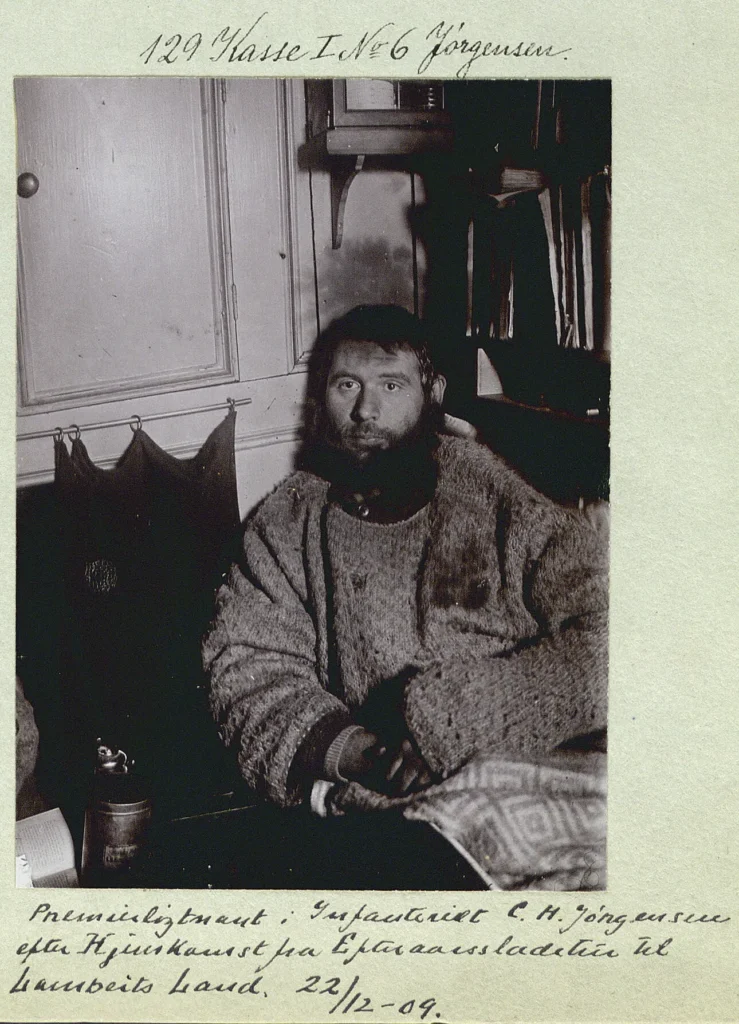

Source: Royal Danish LibraryThe Greenlander they had also employed as a hunter and dog-handler contracted pneumonia and had to be left in the Faroes. Lastly, the ship’s engine failed en route to Greenland, the reason they determined was their incompetent mechanic. Luckily, they were able to call into Iceland, where they found a willing volunteer to replace the mechanic, Iver Iversen. Little did Iversen know about the hardships he would come to suffer over the next few years.

Iversen got the engine running again, and on 25 August the Alabama reached a safe harbour at Shannon Island (75° 12’N), farther south than intended due to the lateness of their arrival to Greenland.

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryIn search of the maps of the perished

Within a month, 3 of the team were sledding their way towards Brønlund’s burial place on Lambert Land (north of 79°N) to see if any trace of Mylius-Erichsen and Høeg-Hagen remained. Neither bodies nor maps were found, and the three returned to the Alabama by Christmas.

Source: Danish Royal Library

Source: Danish Royal Library

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryAlmost immediately, preparations began for the ‘real’ expedition – to sled farther north towards Peary Channel and Danmark Fjord in search of cairns and records hidden within by the previous Denmark Expedition. Caches were laid, and in April, Mikkelsen and Iversen were once again sledding northwards.

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryAt the head of Danmark Fjord, the pair found their prize – the camp where Mylius-Erichsen, Hagen and Brønlund had spent their final summer. Within one of the many cairns nearby they found the following message within a thermometer case:

We…reached Peary’s Cape Glacier and discovered that Peary Channel does not exist, Navy Cliff is joined by land to Heilprin Land…The cairns built here in the vicinity…contain no reports.

Mylius-Erichsen’s note left in Danmark Fjord, 1907.

Source: Ejnar Mikkelsen

Source: Ejnar MikkelsenWith no further information to recover and their objective complete, Mikkelsen and Iversen could return to the ship.

The journey home was extremely arduous; sledding conditions were tough and their dogs eventually all died of exhaustion or were shot for food. Limited hunting meant hunger was a constant threat, but fortunately, they could rely on food caches left by the previous Denmark Expedition. Mikkelsen nevertheless contracted a near-fatal case of scurvy, and twice they accidentally poisoned themselves by eating dog liver.

240 days and 1400 miles (2250 km) after their sled trip had begun Mikkelsen and Iversen finally reached their base. But they found not their ship and their friends as expected – just an empty hut.

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryThe others must have gone. The hut was empty and Iver and I alone in Greenland — east of the sun, west of the moon and in the midst of a white hell.

Mikkelsen writing in 1955.

The hut had been built by their colleagues from the remains of the Alabama after becoming crushed by ice. The rest of the crew had been rescued by a sealing ship months before, presuming Mikkelsen and Iversen to have perished on the ice.

Source: Danish Royal Library

Source: Danish Royal LibraryTwo more winters alone

Mikkelsen and Iversen spent the next two winters in Greenland, surviving largely on a diet of musk ox and supplies left by their crewmates. By all accounts, rather than descending into madness their isolated existence was interspersed by few and relatively minor squabbles.

Source: Royal Danish Library

Source: Royal Danish LibraryOne incident involved a postcard of young women Iversen had within his personal stash. Careful not to touch the girls with their unclean fingers and blur the girls’ features, they spent many hours discussing them. Mikkelsen was especially interested in Miss Steadfast – “a pretty girl in a white dress and a free and easy attitude” – while Iversen’s favourite was Miss Sunbeam who looked “so happy and smiling that it warmed Iver’s all but icy heart”.

One morning while Iversen was cooking porridge, he started to sing a song about Mikkelsen and his sweatheart, Miss Steadfast.

I listened, surprised and rather hurt at my old friend’s complete lack of loyalty; for the song that Iver must have composed during the night was an insult to my honour and that of my girl.

Mikkelsen writing in 1955

The two did not speak until the next day when Iversen passed a note in apology: ‘I am so sorry I took your girl. Take her back, take my four as well, take the whole damned lot — only be cheerful again!’

…we laughed to each other, promising never again to let ourselves be caught in the evil circle of silence, Then Iver cooked a meal of the best the house could produce, which was not very grand.

Mikkelsen writing in 1955

Before the final winter had set in Mikkelsen and Iversen were forced to relocate to the American depot at Bass Rock 30 miles (48 km) to the south where a supply of fuel could be found. To their dismay, they discovered two ships had already searched for them here but had failed to reach the Alabama hut on Shannon Island.

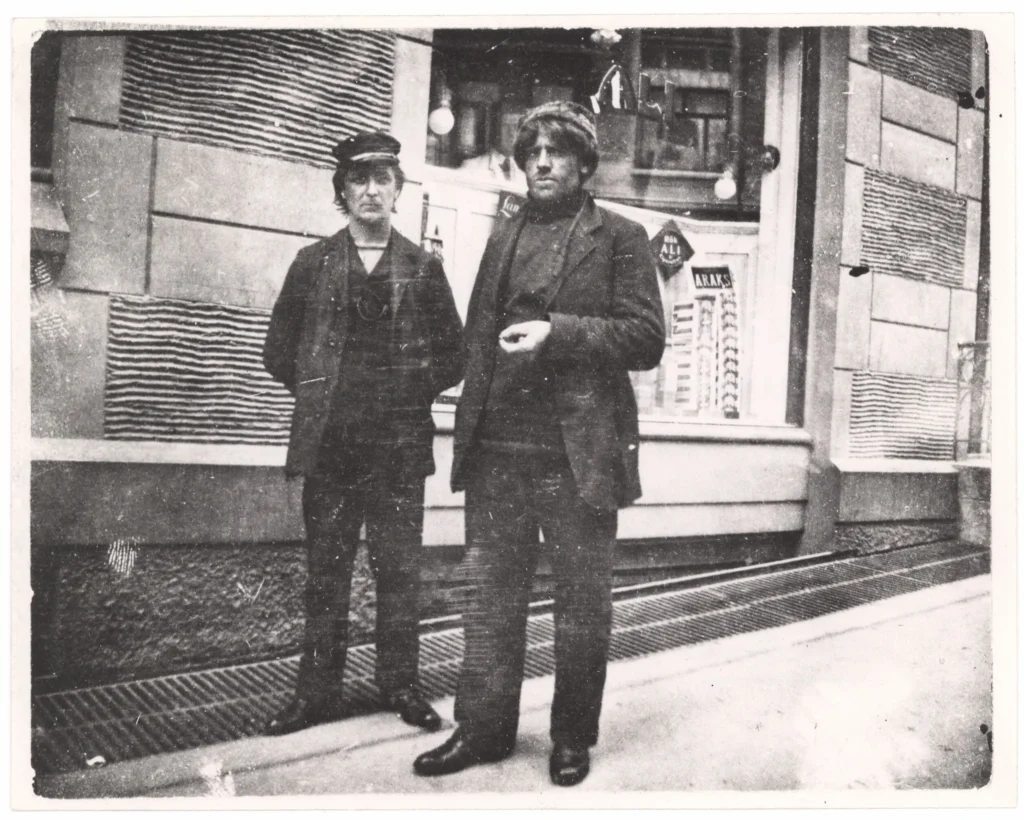

At last, on July 19, 1912, they were awakened by the sound of a commotion outside their hut. Thinking it was a bear, they grabbed their rifles and ran to the door, only to be met by Paul Lillenæs, skipper of Sjøblomsten and his crew: ‘Give us your rifles, boys, we come as friends.’

Source: archive.org

Source: archive.orgThe Peary Channel myth busted

Mikkelsen and Iversen returned to Copenhagen via Norway to a hero’s welcome and were at last reunited with the rest of their friends from the expedition. The news that Peary Channel was indeed a myth thus did not reach the wider world until their return in 1912. This fact was also confirmed by another surveying expedition that same year carried out by Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen.

Ultimately, the United States relinquished its sovereign exploration claims to Greenland in 1917, in conjunction with America’s purchase of the Danish West Indies from Denmark (now the US Virgin Islands).

The Alabama cabin still stands on Shannon Island today, photographed here in 2008.

Source: Henrik Ismarker

Source: Henrik IsmarkerFurther reading:

Koch, L., 1925. The Question of Peary Channel. Geographical Review 15, 643–649. https://doi.org/10.2307/208628

Mikkelsen, E., 1913. Lost in the Arctic : being the story of the “Alabama” expedition, 1909-1912. New York : G.H. Doran.

Mikkelsen Ejnar, 1957. Two Against The Ice. The Travel Book Club London.

Peary, R.E., 1898, Northward over the “great ice” Vol 1. New York, Stokes.

Trolle, A., 1909. The Danish North-East Greenland Expedition. The Geographical Journal 33, 40–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1777751

Against the Ice, 2022. Ill Kippers Productions, RVK Studios.

Be First to Comment