Source: Wikimedia

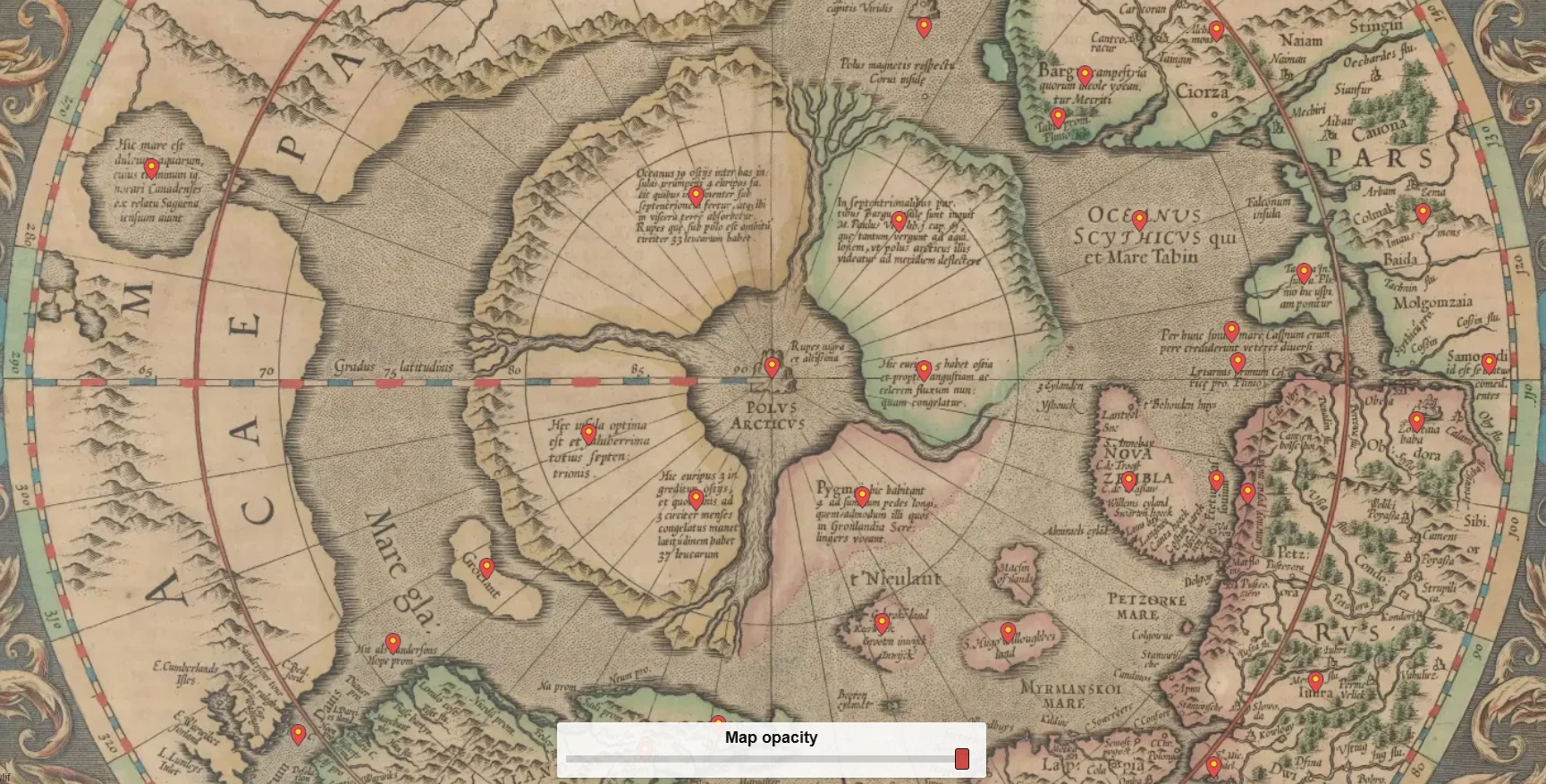

Source: WikimediaGerardus Mercator stands as one of the titans of cartography. Yet, it is one of his later, posthumously published works that presents a fascinating enigma: the Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio of 1595, the first separately printed map dedicated solely to the Arctic regions.

While Mercator was renowned for meticulous research and accuracy, this particular chart of the North Pole offers a vision startlingly unfamiliar to modern eyes. Geographical facts intertwine with centuries-old myths, a product of an age when direct observation of remote regions like the Arctic was exceedingly rare.

Europe’s 16th-Century Arctic Obsession

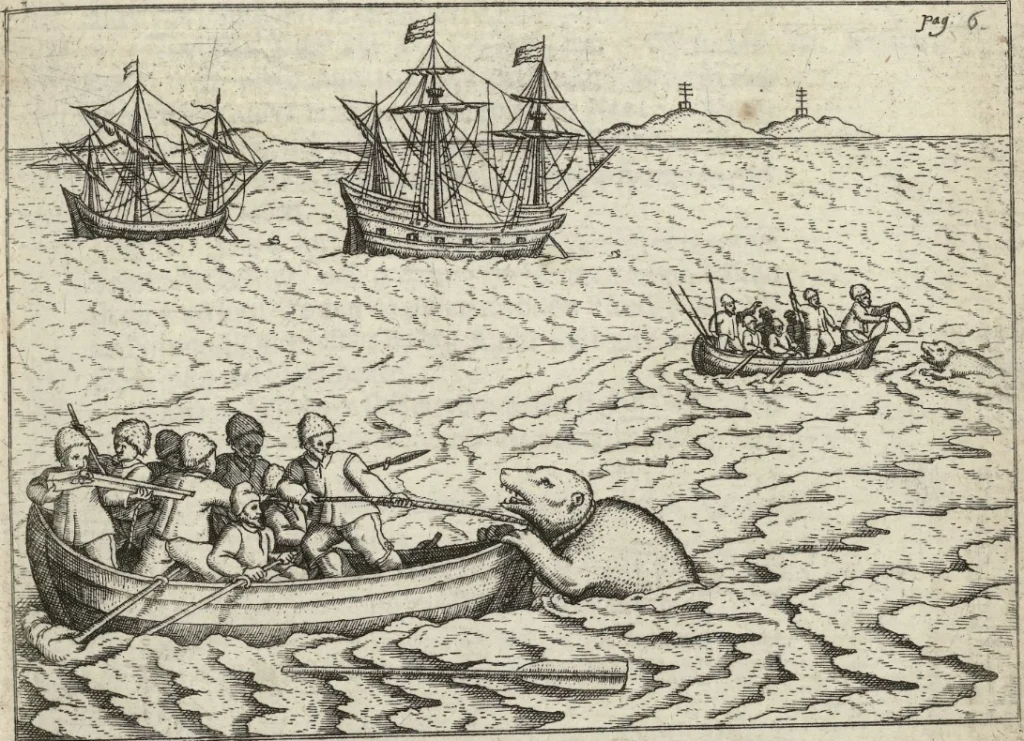

At the time of its first publication in 1595, the Arctic was fast becoming an area of intense interest to European powers, all seeking faster and easier passage to Asian markets via the Northwest around North America, or via the Northeast along the Siberian coast. This economic and geopolitical ambition fueled numerous expeditions, sending explorers like Martin Frobisher, John Davis, and Willem Barents into the icy unknown.

Source: Rijksmuseum

Source: RijksmuseumThese voyages, while often failing to find the desired passages, generated new, albeit sometimes fragmented and misinterpreted, geographical information. This, in turn, created a demand for maps – tools essential for planning future expeditions, for asserting territorial claims, and for disseminating the latest knowledge (or speculation) about these crucial northern waterways.

Mercator’s 1595 map, by depicting features such as the Strait of Anian and implying navigable passages, directly catered to and reinforced these widespread ambitions and reflected the hopes and desires of a continent looking for new pathways to wealth and influence.

Navigating the Myths: What Mercator’s Arctic Got Wrong

While a product of its time, the Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio is laden with features now known to be entirely mythical or significantly misrepresented. For reference, the full 1628 version of this map and its annotations can be explored at https://arctic.rhewlif.xyz.

The Rupes Nigra and the Great Whirlpool

The centerpiece of Mercator’s mythical Arctic was the Rupes Nigra, described as a magnetic rock some 33 French miles in circumference (roughly 180 km in diameter). This feature was thought to be the primary reason compasses pointed north.

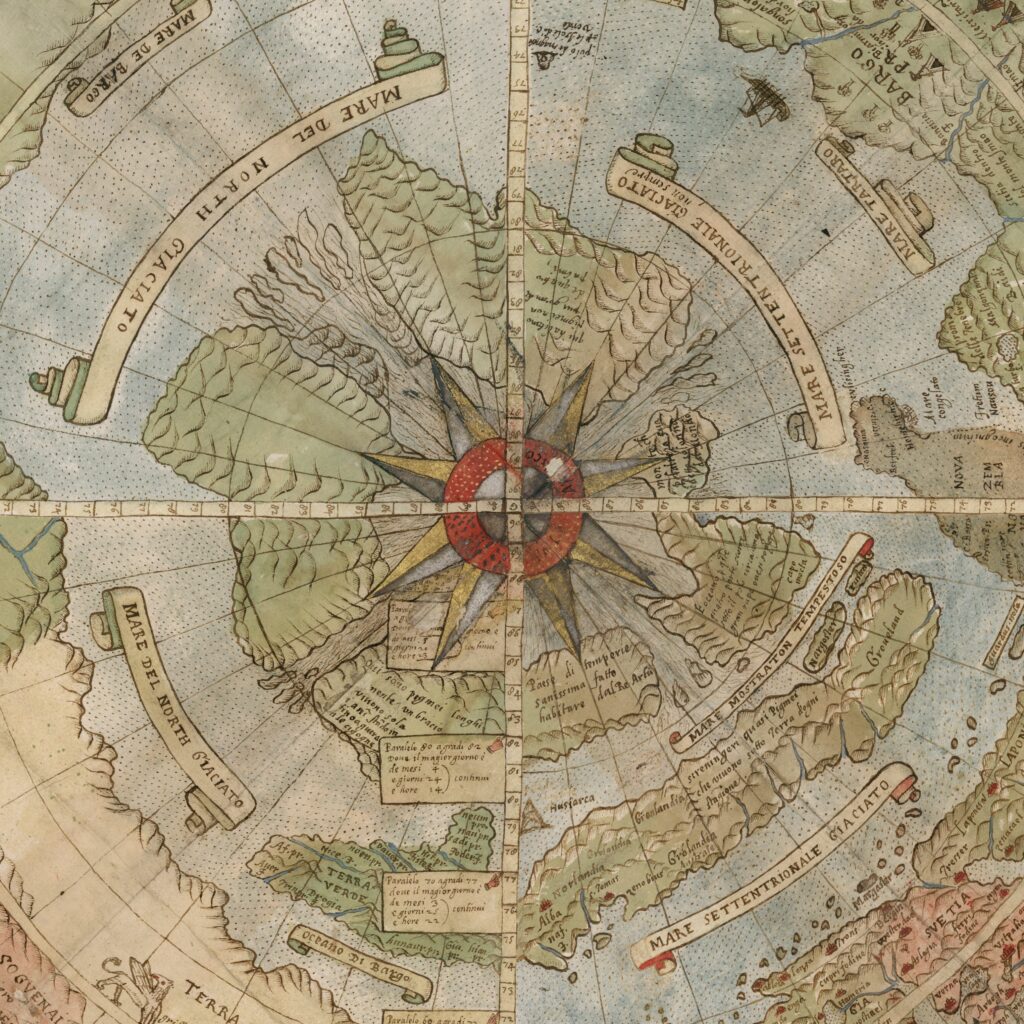

‘Magnetic islands’ was not a new idea, and were featured on earlier maps, for example, shown here on Olaus Magnus’ Carta Marina map of 1539.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaThe depiction of a giant whirlpool, into which four great rivers emptied, is equally dramatic. Mercator himself, in a letter to John Dee, described this maelstrom:

In the midst of the four countries is a Whirl-pool, into which there empty these four indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the Earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel. It is four degrees wide on every side of the Pole, that is to say eight degrees altogether. Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare Rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic Stone (…) This is word for word everything that I copied out of this author (i.e. Cnoyen) years ago.

Mercator, writing to John Dee in 1577

The primary literary source for these dramatic features was the Inventio Fortunata, a supposed 14th-century travelogue by an English friar, which Mercator knew through an account by Jacobus Cnoyen van Herzogenbusch. Both sources are now unfortunately lost to history, yet we see the influence of this text on earlier depictions of the Arctic too, such as Martin Behaim’s globe of 1492 and Urbano Monte’s 1587 map of the world.

Source: gnm.de

Source: gnm.de Source: David Rumsey

Source: David RumseyPhantom Lands and Displaced Peoples

Beyond the central polar features, Mercator’s map is populated with other geographical inaccuracies:

Frisland: This large, entirely mythical island appears prominently south of Iceland and west of Norway, both on the main map and in one of the four corner insets. Its inclusion was a cartographic error perpetuated from the influential, though likely fabricated, Zeno Map of the late 14th century, which Mercator had used for his 1569 world map.

Groclant: Another phantom island, Groclant, is often depicted near Greenland. Its origins are murky, possibly stemming from misinterpretations of early Greenland voyages or even misspellings of “Groenlandt” (Greenland) on earlier charts, leading to the erroneous belief in two separate landmasses. According to Mercator’s 1569 World Map, the inhabitants of Groclant are Swedes by origin.

The Wandering California: The map identifies “California” as Spanish territory but places it remarkably far north above the Arctic Circle, on the western edge of the depicted hemisphere, well above its actual location. This reflects the still-incomplete European understanding of North America’s Pacific coastline.

Gog: Gog and Magog are, respectively, the names of a mysterious people and their Biblical land, who feature in apocalyptic prophecy. By the time of the Roman period, Magog was also associated with the Mongols or Tartars. The legendary Gates of Alexander were thought to be erected by Alexander the Great to repel this tribe.

“Pygmei” in the Arctic: One of the four polar islands, specifically the one in the lower right (closest to Europe), is labelled as being inhabited by “Pygmei,” a race of pygmies supposedly four feet tall. This detail, like the Rupes Nigra, is believed to have originated from the Inventio Fortunata, perhaps a distorted account of indigenous Arctic peoples such as the Inuit or the Saami.

The persistence of such errors, like Frisland, underscores a common characteristic of early cartography: the compounding of mistakes. Mapmakers frequently relied on existing charts for regions unfamiliar to them. If an influential map contained an error, subsequent cartographers, even those as diligent as Mercator, might replicate it, assuming its validity. Once an error was canonised on a map by a respected figure, it gained an aura of authority and was more likely to be copied by others, leading to phantom features haunting maps for centuries.

Glimmers of Truth: What Mercator Got Right(ish)

Despite its fantastical elements, the Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio was not without its merits and represented significant advancements for its era.

The First Dedicated Arctic Map

The map’s foremost achievement was its status as the first stand-alone chart devoted exclusively to the Arctic regions. Prior to this, the Arctic was typically shown, if at all, as part of larger world maps.

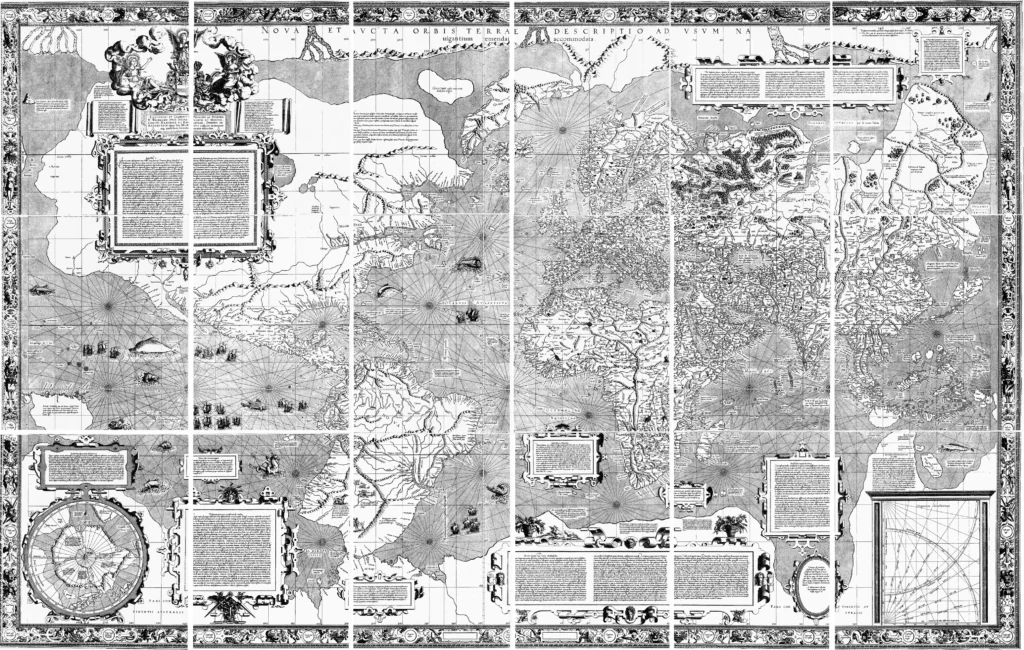

Mercator’s own famous 1569 world map, utilizing his revolutionary projection, inherently distorted the polar areas to an extreme degree, making them practically infinite in height.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaThis 1595 polar projection map was, in part, a necessary clarification and expansion of the small Arctic inset included on that earlier world map, offering a more practical and focused view of the top of the world.

Embracing New Discoveries

Mercator was keen to incorporate the latest available information from contemporary explorers. His Arctic map includes details from the voyages of Martin Frobisher and John Davis, English mariners who undertook expeditions in the 1570s and 1580s searching for a Northwest Passage.

Features such as “Fretum Forbosshers” (Frobisher Strait) and “Fretum Dauis” (Davis Strait), as well as “E. Cumberlands Isles” (Cumberland Sound, explored by Davis) and Sanderson’s Hope (the high latitude of 72° 12′ N reached by Davis) are testaments to this effort.

The map also names “S. Hugo Willoughbes land” in the east, after Sir Hugh Willoughby’s ill-fated 1553 expedition, and shows early indications of Dutch explorations around Novaya Zemlya, which would be further clarified in later editions by Jodocus Hondius following Willem Barentsz’s significant discoveries.

Source: Stanford University

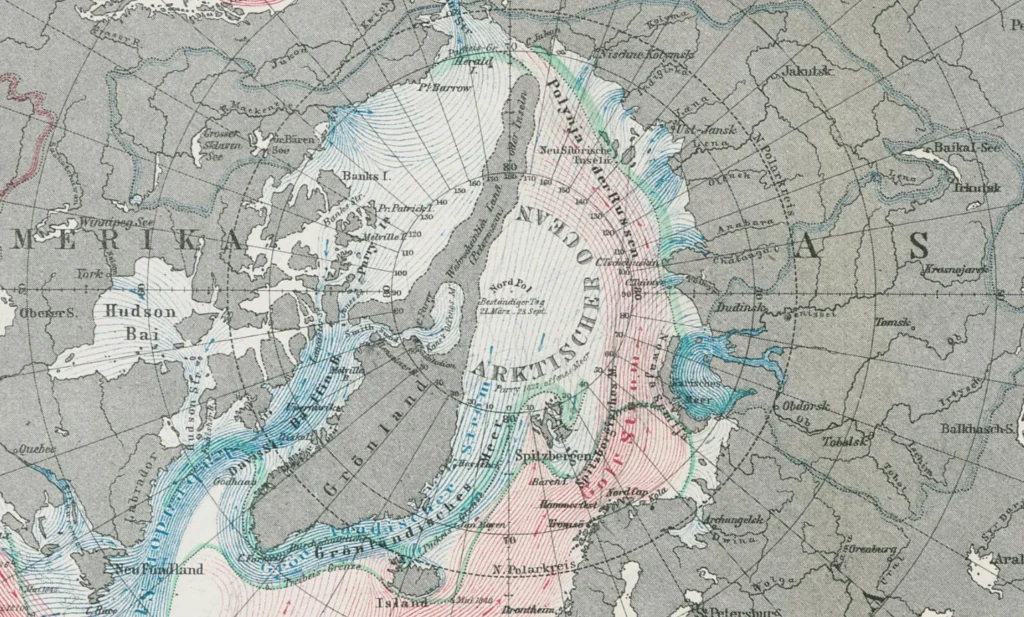

Source: Stanford UniversityThe Open Polar Sea

While the four islands surrounding the Rupes Nigra were pure fantasy, the map’s depiction of an open, potentially navigable sea in the high Arctic, rather than a solid polar continent, was, as some scholars note, “accidentally correct”. This notion of an open polar sea, though embedded within a mythical framework, proved more accurate than alternative theories of a contiguous polar landmass.

Nearly three centuries later, the still limited penetration by explorers into the High Arctic meant creative ideas of an extensive land mass across the North Pole were still being floated, for example, by August Petermann in 1865.

Source: Erfurt University

Source: Erfurt UniversityGrappling with Magnetism

Although the Rupes Nigra as the sole source of magnetism was incorrect, Mercator’s cartography shows an engagement with the complex problem of magnetism and compass variation. Even in the late 16th century, sailors often found that their compasses increasingly deviated from ‘true north’.

Although many believed the rock at the North Pole to be magnetic, Mercator preferred to place a magnetic rock near the Strait of Anian, in an attempt to explain the magnetic variation. Two poles are proposed, the first with respect to a meridian through the Cape Verde islands, and an alternative pole with respect to a meridian through the island of Corvo (Azores).

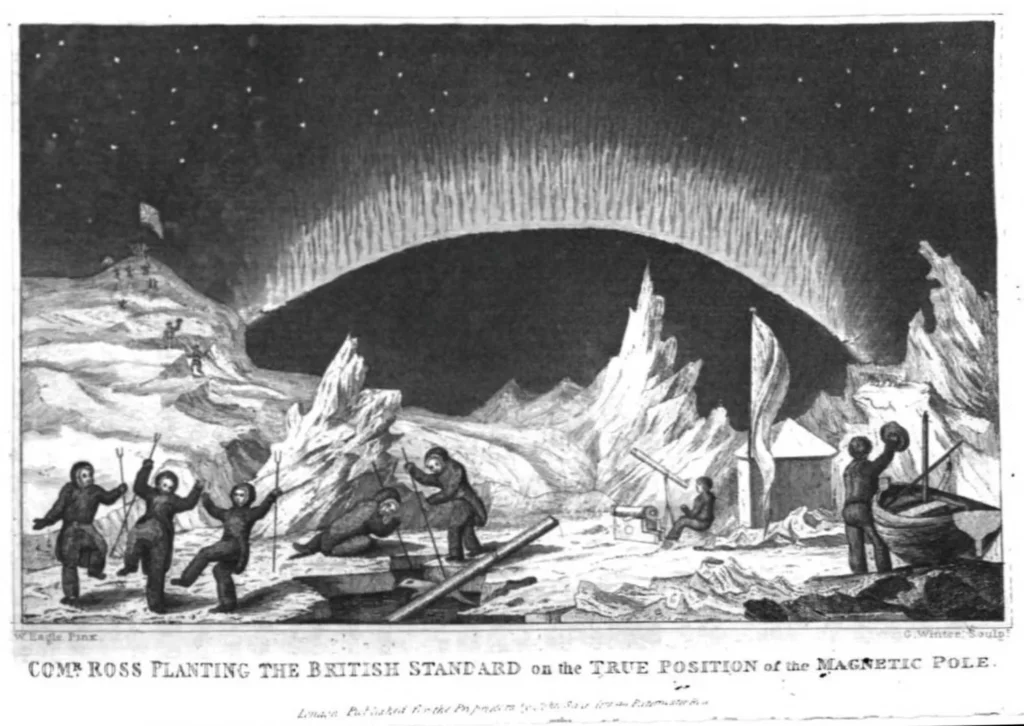

The location of the North Magnetic Pole was discovered much later in 1831 by James Clark Ross, on the Boothia Peninsula in the far north of Canada.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaThe Enduring Legacy of a Mythical North

Given Gerard Mercator’s towering reputation, his depiction of the Arctic, myths and all, exerted considerable influence on subsequent cartography and popular imagination for decades aftewards. The “demythologizing” of the Arctic was a gradual process, driven by the increasing number of voyages by explorers, whalers, and traders who brought back more reliable, firsthand observations.

Jodocus Hondius, who acquired Mercator’s copper plates in 1604, began to issue updated states of the map. These later editions showed evolving coastlines, particularly for areas like Spitsbergen (following Barentsz’s discoveries) and Novaya Zemlya, and even began to alter the outlines of the mythical polar islands themselves, sometimes showing them as incomplete as new information trickled in. For example, the first edition (1595) shows a definitive coastline for the “Pygmei” island, while later editions omit part of this coastline.

Gerard Mercator’s 1595 Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio stands as a remarkable testament to the cartographic endeavours of the late 16th century. It was a groundbreaking achievement as the first map dedicated exclusively to the Arctic, a bold attempt to chart one of the Earth’s still great unknowns, incorporating the most recent exploratory data available. Simultaneously, it is a fascinating tapestry woven from medieval myths, ancient legends, and contemporary geographical theories, a world where magnetic mountains, polar whirlpools, and phantom islands held sway.

Be First to Comment