High up on the Glockenspiel House in Bremen, Germany, today, can be found a curious wood carving showing two sailors meeting a Native American. This is the story of how two German privateers sailed to North America two decades before Columbus had ‘discovered’ the continent. However, this saga represents a complex historical controversy, resting more on cartographic inference, circumstance, and nationalistic ambition than verifiable documentation.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaTrade Wars and the Arctic Frontier

The central characters of this story are two renowned 15th-century German pirates: Didrik Pining and his partner-in-crime, Hans Pothorst. In the 1470s, they were hired into the service of King Christian I of Denmark to lead an expedition to Iceland and Greenland with a clear, strategic goal: to investigate Arctic trade policies to counter the monopoly held by the Hanseatic League and England.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaHowever, Pining’s official mandate extended beyond Iceland. He was specifically ordered to investigate the regiones finitimae – Latin for “the coasts opposite those still-remembered but obsolete settlements in Greenland”.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaThe focus was not on random discovery, but on the calculated re-establishment of territorial claims based on ancient Norse history, underscoring a Danish attempt to reclaim sovereignty over the North Atlantic frontier.

According to the story, Pining and Pothorst were joined by João Vaz Corte-Real from Portugal and the enigmatic John Scolvus, who served as navigator. Together, they became the first Europeans to see North America since the Viking Age.

The “German discovery” narrative emerges

If Pining and others had discovered North America, they certainly didn’t write about it in any document known today. In fact, it was not until 1925 that the Danish librarian at the University of Copenhagen, Sofus Larsen, first pieced together the hypothesis. His arguments drew on three main lines of evidence.

1. The Hvitsarc enigma

A key document central to our understanding of this voyage was discovered in 1909 in the Danish state archives. It was a letter written by Carsten Grip, Bürgermeister of Kiel, to King Christian III of Denmark in March 1551. In it, he recalls a map just published in Paris and casually mentions

“…that the two skippers, Pyningk [Pining] and Poidthorsth [Pothorst], who were sent out by your majesty’s royal grandfather, King Christian the First, at the request of his majesty of Portugal with certain ships to explore new countries and islands in the north have raised on the rock Wydtheszerck [Hvitserk], lying off Greenland and towards Sniefeldsiekel in Iceland on the sea, a great sea-mark on account of the Greenland pirates, who with many small ships without keels fall in large numbers upon other ships,…”

Carsten Grip, March 3, 1551

As King Christian I died in 1481, this joint Portuguese-Danish expedition must have gone out before that date. Indeed, these two maritime powerhouses were on good political terms during this period.

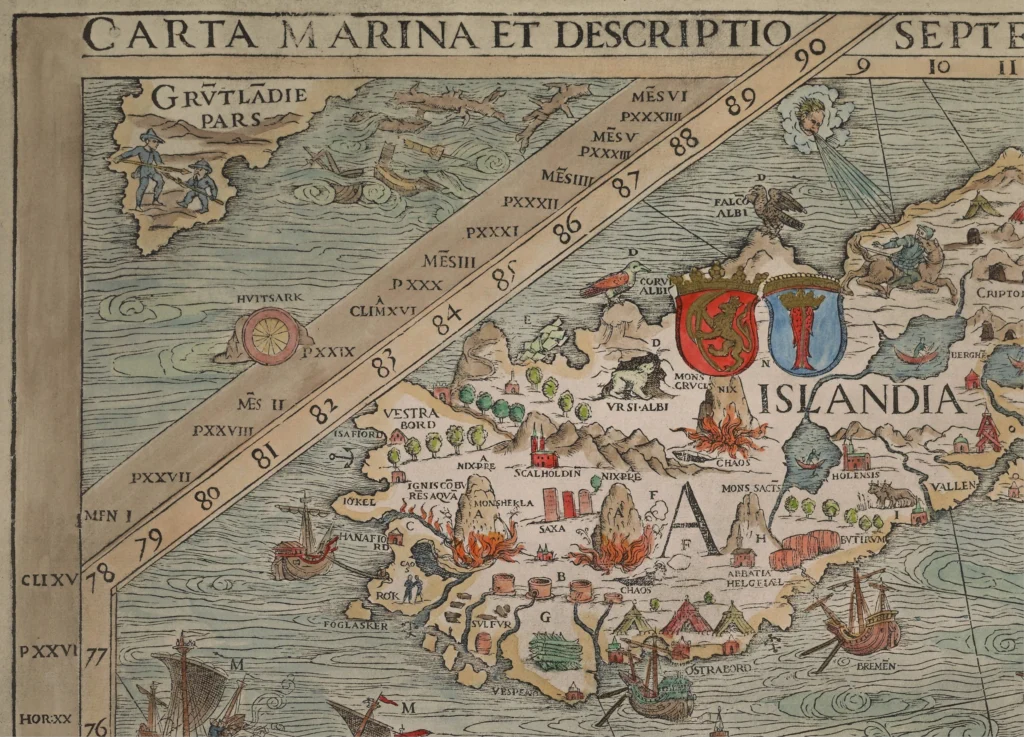

Olaus Magnus, the Swedish ecclesiastic, had noted the story of Hvitsarc on his iconic 1539 Carta Marina and 1555 accompanying narrative, depicting the giant sea-mark as a compass.

Source: University of Minnesota

Source: University of MinnesotaHvitsarc similarly appears on a 1532 German map, as well as a 1548 copy of the Iceland section of Carta Marina by Hieronymus Gourmont, which includes a similar origin story for the Hvitsarc sea-mark built by these two privateers. This 1548 version is possibly the map Carsten Grip referred to in his letter.

Source: UiT

Source: UiT Source: islandskort.is

Source: islandskort.is2. A Portuguese participant?

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaRepresenting Portuguese interests on the joint expedition was João Vaz Corte-Real. Historical Portuguese documents noting Corte-Real “arriving from the Terra do Bacalhao (the land of codfish, i.e. Newfoundland), which he went to discover by order of the king”, were used by Larsen to conclude that, along with Pining and Pothorst, Corte-Real had indeed reached the cod-rich waters off North America.

In 1474, Corte-Real was appointed Governor of half of Terceira island in the Azores, as argued by Larsen, a reward for his services to the crown. Coincidentally, Pining received a similar rise in status, around this time too, becoming the Governor (höfuðsmaðr) of Iceland in 1478.

Further connections linking Corte-Real can be found in the depiction of lands west of Greenland on Behaim’s 1492 Erdfapel – the oldest surviving globe – bearing an uncanny resemblance to the islands of Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and the Gulf of St Lawrence. With the globe produced before Behaim knew anything of Columbus’ voyage that same year, it has been argued that Corte-Real was the anonymous source for these islands.

Source: David Rumsey

Source: David Rumsey Source: LoC

Source: LoCFrom 1486 to 1490, Behaim actually resided on the same island of Terceira where Corte-Real was governor. Furthermore, Behaim married a sister of Corte-Real’s son-in-law. Opportunity to share secret knowledge, therefore, certainly existed.

Also of note, another map where the name of João Vaz Corte-Real does appear in North America is in a 1576 atlas by Portuguese cartographer Fernão Vaz Dourado. Here, two features are directly named after him: a point of land and a bay on the coast of Labrador.

3. A mystery navigator

A final cartographic clue to an early expedition beyond Greenland can be found on the terrestrial globe created by Gemma Frisius in 1536. On it, a westward passage north of Labrador carries the inscription:

“The people Quij, to whom the Dane Johannes Scolvus penetrated about the year 1476”

(Quij populi ad quos Joannes Scolvus, danus, pervenit circa annum 1476).

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaWas Scolvus also part of the same expedition led by Pining and Pothorst?

According to Larsen, yes. This enigmatic navigator has courted many theories from historians over the decades, though there is no agreement about his background or even which country he hailed from. One historian even proclaimed him to be Columbus himself.

Regardless of who he was, the annotation adds further circumstantial weight to a voyage of exploration in the 1470s that supposedly penetrated far to the west.

20th-century scepticism

Nevertheless, modern scholarship remains sceptical, viewing the claim of a successful transatlantic crossing by Pining and Pothorst as highly unlikely. Yet there is a wider agreement that a voyage led by Pining and Pothorst reached Greenland, possibly with Corte-Real and Scolvus on board.

A major counter-argument for the group not reaching America is the rigid time constraints set by the participants’ activities elsewhere. One document shows Pothorst was in service on the warship Bastian until 1 July 1473, while Corte-Real was presumably back in Portugal in January 1474 to take on his new role as Governor in the Azores. Six months, in early winter, is argued to be too short a window to reach Newfoundland from Europe.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: WikimediaUltimately, archaeological evidence unearthed in the 1960s has confirmed that the true priority for European contact belongs to the Norse seafarers, such as Leif Eriksson, whose settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland dates back to circa 1000 CE. The deepest historical priority belongs to the ancestors of Native Americans, who crossed the Bering land bridge approximately 15,000 years ago.

The voyage’s legacy

Source: Medieval Histories

Source: Medieval HistoriesBoth Pining and Pothorst achieved significant status through their service to the Danish Crown. Pothorst, in particular, must have accumulated considerable wealth, evidenced by his coat of arms and his purported donation funding murals in St. Mary’s Church in Elsinore around 1493.

Pining’s career culminated in 1478 when he became the governor of Iceland, from which post he exercised major political influence in both Iceland and Norway. Despite their elevated positions, their lives remained precarious; a later chronicle recounts that both men “met with a miserable death, being either slain by their friends or hanged on the gallows or drowned in the waves of the sea”.

After Larsen published his radical theory in 1925, the claim was rapidly appropriated and instrumentalised by various national interests seeking to establish pre-Columbian priority.

The discovery that the heroes were, in fact, German was made only a few years later in 1933. A genealogical study showed Pining to be a German native of Hildesheim, near Bremen. Pothorst also probably grew up as a neighbour in this small town.

And so the narrative was formalised and absorbed into public consciousness, with streets in both Bremen and Hildesheim being named in honour of the buccaneers. The wood carving of Pining and Pothorst was also built into the Glockenspiel House in Bremen in 1934.

Source: Google

Source: GoogleDespite this story being a prime example of a historical saga built on circumstance, the core facts involving German pirates serving a Danish king to patrol the Greenland-Icelandic frontier in the 1470s remain relatively solid. Maybe one day, another dusty manuscript will be found in the Portuguese or Danish archives that will provide the final proof of a transatlantic discovery.

Further reading

Hughes, T.L., 2004. “The German Discovery of America”: A Review of the Controversy over Pining’s 1473 Voyage of Exploration. German Studies Review 27, 503–526.

Larsen, S., 1925. The discovery of North America twenty years before Columbus. Levin & Munksgaard, Copenhagen. (US Public Domain)

Be First to Comment